By 1881, the Italian author Carlo Collodi had already achieved renown as a translator of fairy tales when friends piqued his interest in writing his own. A short story about a little wooden puppet come to life was published in the children’s section of a Roman newspaper, which evolved into the serialized Adventures of Pinocchio. The first 15 episodes ran through 1881 and 1882 before Collodi was invited to write an additional 21 chapters for publication in a book in 1883.

In the original serialized form, Pinocchio is an outright brat whose short life ends with being hanged until dead at the conclusion of chapter 15. Collodi dispenses with trying to explain how Pinocchio is alive. Much like ourselves, he merely is and the rest must suffer the consequences. Among his miscreant acts is to flee from Geppetto the moment he is given legs, squish the Talking Cricket that tries to moralize at him, sell off the A-B-C book that Geppetto bought for him (by trading off his only coat) in exchange for tickets to the Marionette Theater, and finally to run afoul of the Fox and the Cat, who are ultimately responsible for his assassination. Pinocchio's was a hard life poorly spent and easily lost.

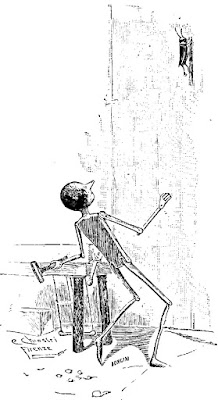

|

| Fleeing from Geppetto. Illustration by Carlo Chiostri. |

The Talking Cricket does show up throughout the book in one form or another. This excerpt of chapter four tells of their disastrous first meeting:

On reaching home, he found the house door half open. He slipped into the room, locked the door, and threw himself on the floor, happy at his escape.

But his happiness lasted only a short time, for just then he heard someone saying:

"Cri-cri-cri!"

"Who is calling me?" asked Pinocchio, greatly frightened.

"I am!"

Pinocchio turned and saw a large cricket crawling slowly up the wall.

"Tell me, Cricket, who are you?"

"I am the Talking Cricket and I have been living in this room for more than one hundred years."

"Today, however, this room is mine," said the Marionette, "and if you wish to do me a favor, get out now, and don't turn around even once."

"I refuse to leave this spot," answered the Cricket, "until I have told you a great truth."

"Tell it, then, and hurry."

"Woe to boys who refuse to obey their parents and run away from home! They will never be happy in this world, and when they are older they will be very sorry for it."

"Sing on, Cricket mine, as you please. What I know is, that tomorrow, at dawn, I leave this place forever. If I stay here the same thing will happen to me which happens to all other boys and girls. They are sent to school, and whether they want to or not, they must study. As for me, let me tell you, I hate to study! It's much more fun, I think, to chase after butterflies, climb trees, and steal birds' nests."

"Poor little silly! Don't you know that if you go on like that, you will grow into a perfect donkey and that you'll be the laughingstock of everyone?"

"Keep still, you ugly Cricket!" cried Pinocchio.

But the Cricket, who was a wise old philosopher, instead of being offended at Pinocchio's impudence, continued in the same tone:

"If you do not like going to school, why don't you at least learn a trade, so that you can earn an honest living?"

"Shall I tell you something?" asked Pinocchio, who was beginning to lose patience. "Of all the trades in the world, there is only one that really suits me."

"And what can that be?"

"That of eating, drinking, sleeping, playing, and wandering around from morning till night."

"Let me tell you, for your own good, Pinocchio," said the Talking Cricket in his calm voice, "that those who follow that trade always end up in the hospital or in prison."

"Careful, ugly Cricket! If you make me angry, you'll be sorry!"

"Poor Pinocchio, I am sorry for you."

"Why?"

"Because you are a Marionette and, what is much worse, you have a wooden head."

At these last words, Pinocchio jumped up in a fury, took a hammer from the bench, and threw it with all his strength at the Talking Cricket.

Perhaps he did not think he would strike it. But, sad to relate, my dear children, he did hit the Cricket, straight on its head.

With a last weak "cri-cri-cri" the poor Cricket fell from the wall, dead!

|

| The Talking Cricket about to meet his end. Illustration by Carlo Chiostri. |

When Walt Disney adapted The Adventures of Pinocchio into their second animated feature film, they made the choice to soften Pinocchio's character into something considerably more likeable, whose adventures were considerably less violent. The original story developed out of Italian satirical writing and the commedia dell'arte theatre tradition. This form of theatre, in which the actors wear masks and gaudy costumes, evolved into pantomime and marionette forms from which the Punch and Judy puppet show is derived. This lineage is referenced in the story, when Pinocchio visits the Marionette Theater run by Mangiafuoco (whose name literally translates to "Fire-Eater" and whose nickname is "Stromboli") and sees marionettes of Harlequin and Pulcinella perform. Both are stock characters in commedia dell'arte, and Pulcinella is the original form of Punch.

A typical Punch and Judy show begins with Judy leaving their baby in the care of Punch, who carries a stick as large as himself that he uses as his all-purpose tool for problem solving. When Judy returns to find Punch variously beating their baby, tossing it around, or literally baby-sitting, a donnybrook ensues that eventually consumes the entire neighbourhood. Everyone from policemen to the Devil himself fall victim to Punch's free-swinging baton. These shows, for the most part, are intended as hysterical entertainment without overt moralizing… Punch's baton is even called the "slapstick." It is easy to see how this sort of puppet show is reflected in The Adventures of Pinocchio's unending stream of violence and absurdities.

|

| Pinocchio hangs. Illustration by Carlo Chiostri. |

When it came time to collect the serial as a full novel, Pinocchio was given a second chance. Rather than suffer an ignoble death, the Fairy with Turquoise Hair rescues him and seeks to set him right. Once again, Pinocchio cannot resist temptations offered by the Fox and Cat. Every time he seeks to better himself and follow the rules and go to school like a good boy should, something else comes up to prey on his moral failings. Pleasure Island and Monstro the Whale were inspired by this latter half, though in their original forms they are the Land of Toys and a giant shark or dogfish.

Unlike the ribald marionette shows from which The Adventures of Pinocchio comes, Collodi does succumb to moralizing. The question stands as to whether or not this book is (or ever was) wholly appropriate for children. When it was to be published in book form, perhaps Collodi felt that he needed to make it morally edifying. Careful readers may detect that Collodi is taking himself more seriously in the book's latter half, in longer chapters that appear more carefully thought out.

All 36 chapters of the original story in an 1926 English translation can be found at Project Gutenberg.

No comments:

Post a Comment